Hot Press, February 23, 1989: Difference between revisions

(+text part 3) |

(+text part 4) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

"The press were looking for something to crucify me with, and I fed myself to the lions," said the singer in a rare 1982 ''[[Rolling Stone, September 2, 1982|Rolling Stone]]'' interview, referring to the petty, drunken argument with Bonnie Bramlett, when Elvis shot his mouth off about black music and then was forced to duck as American journalists returned fire. ELVIS COSTELLO REPENTS said the cover headline over a photo of a completely unpenitent pop-star, gazing suspiciously out through large, black-rimmed spectacles, as if irritated at having to break his self-imposed silence to explain off the unfortunate and unwarranted stigma of racism that was then still damaging his American career. I looked up from the page... and straight into the same face gazing vacantly back at me from across the departure lounge. | "The press were looking for something to crucify me with, and I fed myself to the lions," said the singer in a rare 1982 ''[[Rolling Stone, September 2, 1982|Rolling Stone]]'' interview, referring to the petty, drunken argument with Bonnie Bramlett, when Elvis shot his mouth off about black music and then was forced to duck as American journalists returned fire. ELVIS COSTELLO REPENTS said the cover headline over a photo of a completely unpenitent pop-star, gazing suspiciously out through large, black-rimmed spectacles, as if irritated at having to break his self-imposed silence to explain off the unfortunate and unwarranted stigma of racism that was then still damaging his American career. I looked up from the page... and straight into the same face gazing vacantly back at me from across the departure lounge. | ||

The face was a little heavier maybe, slightly bearded, sporting small, rounded, dark glasses and with a black cap pulled low on the forehead as if making a half-hearted attempt at celebrity disguise, but it was him alright. Elvis Costello, in person, his wife Cait sitting to his right, a WEA International rep to his left. Carefully folding my clippings, I ambled over to introduce myself. | The face was a little heavier maybe, slightly bearded, sporting small, rounded, dark glasses and with a black cap pulled low on the forehead as if making a half-hearted attempt at celebrity disguise, but it was him alright. Elvis Costello, in person, his wife [[Cait O'Riordan|Cait]] sitting to his right, a WEA International rep to his left. Carefully folding my clippings, I ambled over to introduce myself. | ||

Elvis saw me coming. Or rather, he saw someone making a bee-line for him, clutching Costello cut-out pictures. His eyes darted to the left and right, as if seeking a convenient escape route, but he was against the wall and far from any crowd. Realising he was trapped, he slumped in his seat and attempted a weak smile as he accepted my outstretched hand. Cait buried her face in a book, keen to avoid the homily of an ardent fan. | Elvis saw me coming. Or rather, he saw someone making a bee-line for him, clutching Costello cut-out pictures. His eyes darted to the left and right, as if seeking a convenient escape route, but he was against the wall and far from any crowd. Realising he was trapped, he slumped in his seat and attempted a weak smile as he accepted my outstretched hand. Cait buried her face in a book, keen to avoid the homily of an ardent fan. | ||

"I'm from Hot Press," I said, "I thought you were supposed to be in Dublin!" "You're the one who's supposed to be in Dublin," countered Elvis, understandably mystified. "What's going on?" asked the bewildered WEA rep. | "I'm from ''Hot Press''," I said, "I thought you were supposed to be in Dublin!" "You're the one who's supposed to be in Dublin," countered Elvis, understandably mystified. "What's going on?" asked the bewildered WEA rep. | ||

The flight was announced as we gave our conflicting explanations of the communications complication that led to two people who lived in the same city flying all the way to another country to meet one another. "Bizarre!" laughed Elvis. "Why doesn't anybody ever tell me what's going on?" complained the rep. "Don't worry," says Elvis, "I've got some other things I've got to do over there." "All it takes is a phone call!" muttered the rep, despairingly. "See you in Dublin," smiled Elvis as we boarded. | The flight was announced as we gave our conflicting explanations of the communications complication that led to two people who lived in the same city flying all the way to another country to meet one another. "Bizarre!" laughed Elvis. "Why doesn't anybody ever tell me what's going on?" complained the rep. "Don't worry," says Elvis, "I've got some other things I've got to do over there." "All it takes is a phone call!" muttered the rep, despairingly. "See you in Dublin," smiled Elvis as we boarded. | ||

| Line 37: | Line 38: | ||

He toured sporadically with the loose collection of ''King Of America'' session men The Confederates, "a difficult band to get together in one place at one time." He did get them together in Europe, then later in the southern states of America, in Australia and Japan. "I wanted to play down south with those guys just to see what happened," he says. They played Honky Tonks in Tulsa, New Orleans and Nashville where, he confesses, "the audiences were completely bewildered because they have a force-fed diet of that kind of music, and R'n'B and country, and when I go down there they kind of want punk rock or something!" | He toured sporadically with the loose collection of ''King Of America'' session men The Confederates, "a difficult band to get together in one place at one time." He did get them together in Europe, then later in the southern states of America, in Australia and Japan. "I wanted to play down south with those guys just to see what happened," he says. They played Honky Tonks in Tulsa, New Orleans and Nashville where, he confesses, "the audiences were completely bewildered because they have a force-fed diet of that kind of music, and R'n'B and country, and when I go down there they kind of want punk rock or something!" | ||

In '87 he also did a solo college tour in America and then came to Ireland and lived in The Gresham for three months while | In '87 he also did a solo college tour in America and then came to Ireland and lived in The Gresham for three months while Cait was acting in the film ''The Courier''. Elvis kept himself busy writing songs ("I must have written about half this album next door," he recalls) and got talked into doing the music for the film, which he found "quite therapeutic not having to worry about song structures." ''The Courier'' got released in '88 to quite an overwhelmingly negative reception -- Elvis thought that unfair: "It wasn't ''Citizen Kane'' but I don't think its makers thought it was." He did some work with Latin American star Reuben Blades, co-writing songs on his first English language album, played with a veritable galaxy of stars backing Roy Orbison for a special concert and, out of the blue, was asked if he would like to do some writing with Paul McCartney. | ||

They had met on a few occasions in studios and on benefit shows, but, as Elvis wryly observes, "He's not the sort of guy you go knocking on his door saying 'Can I write some songs with you?'" A huge Beatles fan, Elvis had never really disparaged McCartney's solo work as many of his punk contemporaries had. "Even at his most nursery rhymish, there was always something musically redeeming in his songs. I learned a tremendous amount from The Beatles and it's in my songs, it's in me, and he's one half of the partnership that put it there in the first place." | They had met on a few occasions in studios and on benefit shows, but, as Elvis wryly observes, "He's not the sort of guy you go knocking on his door saying 'Can I write some songs with you?'" A huge Beatles fan, Elvis had never really disparaged McCartney's solo work as many of his punk contemporaries had. "Even at his most nursery rhymish, there was always something musically redeeming in his songs. I learned a tremendous amount from The Beatles and it's in my songs, it's in me, and he's one half of the partnership that put it there in the first place." | ||

| Line 61: | Line 62: | ||

There was no musical rebellion or generation gap antagonism in the MacManus household. "I never thought of rock 'n' roll as being particularly rebellious," says Elvis. "The first pop music I really identified with was The Beatles when I was eight or nine and most everybody of all generations, could appreciate that the Beatles were good. Most of the time I was in agreement with my father, not about the songs he necessarily liked but about the songs that he sang. Back in 1963, you got like two hours a week when you heard pop music on the radio and the rest of the time it was light orchestra music, you know swing, dance band music. And the more hip dance bands started to play the modern music, doing modified arrangements. The publishers were putting out records as fast as they could, trying to get covers, cause that was the way people had hits -- it wasn't necessarily through the original artist, it was by people becoming familiar with the song. The song was still king. It was The Beatles that changed that, playing their own instruments. | There was no musical rebellion or generation gap antagonism in the MacManus household. "I never thought of rock 'n' roll as being particularly rebellious," says Elvis. "The first pop music I really identified with was The Beatles when I was eight or nine and most everybody of all generations, could appreciate that the Beatles were good. Most of the time I was in agreement with my father, not about the songs he necessarily liked but about the songs that he sang. Back in 1963, you got like two hours a week when you heard pop music on the radio and the rest of the time it was light orchestra music, you know swing, dance band music. And the more hip dance bands started to play the modern music, doing modified arrangements. The publishers were putting out records as fast as they could, trying to get covers, cause that was the way people had hits -- it wasn't necessarily through the original artist, it was by people becoming familiar with the song. The song was still king. It was The Beatles that changed that, playing their own instruments. | ||

"So I had a big stack of A-label records, acetates of all kinds of stuff that my dad was obliged to learn. He's a very versatile singer and quite a good mimic and they had a tremendously imaginative arranger who somehow managed to score these pop records for this 14-piece orchestra. Now whether my father liked it or not I don't know. I'm sure some of the songs he hated, but he got lumbered with this, doing things like "Good Vibrations" and "Like A Rolling Stone". | |||

Elvis can only remember rebelling against his father's tastes in the late '60s, when MacManus senior was becoming a little too radical for his son. "My father sort of became like a hippy, when he was about 40. He grew his hair and he started listening to The Jefferson Airplane and things, and that was the only time we disagreed about music. I didn't like all that stuff. He gave me a load of psychedelic records and I was into Tamla Motown by then." | |||

It was a time when Elvis recalls his own tastes developing and changing. "As a teenager things change very quickly for you, sometimes yon feel brasher and I liked Tamla Motown and other times you get all angst-ridden and I liked [[Joni Mitchell]] or something. Then as you get older and you're writing yourself you become aware that this music isn't just something that is done to you, you can actually control it. Music stops being this magic thing that appears out of nowhere, you can dismantle it and find out how it works and use it as a language. Yet when it gels, it's still really magical. I wrote some quite sophisticated songs in my teens. "New Lace Sleeves," which turned up on ''Trust'', I'd written that when I was 19. So you obviously incorporate a lot of things you've learned as a listener. And I know a lot of music. I've memorised it, I know more songs than most people I know. | |||

Ross MacManus still performs, and has been known to include an occasional Elvis Costello song in his set. "We've sung together," says Elvis, with obvious pride. "I was on a show, a celebration of the Joe Loss Orchestra and my dad was invited back to sing on the BBC. We did "Georgia" together." | |||

Digging deeper into the MacManus family background, Elvis reveals that his grandfather was 'a military trained classical player.' He also has four half-brothers from his father's second marriage "and they're mostly musical as well." He's not convinced it's a genetic thing, however. "I don't hold with those theories. The difference in musical experience between my father, my grandfather and myself is quite a lot. And my great grandfather was a coal merchant so I don't know what his input is!" | |||

Elvis has a son by his first marriage, who is now 14 and into speed-metal and rap. Elvis doesn't think it too likely he will be the successor in a musical dynasty. "It's less dominant in his life than it was in mine," he comments. "He's tinkered around with something musical. He hasn't shown me. He's kind of interested more in art." | |||

| Line 82: | Line 93: | ||

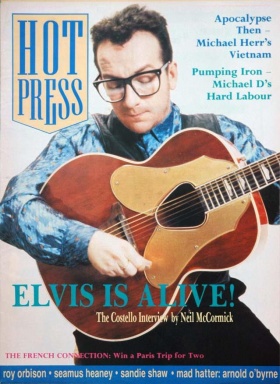

[[image:1989-02-23 Hot Press cover.jpg|280px|border]] | [[image:1989-02-23 Hot Press cover.jpg|280px|border]] | ||

<br><small>Cover.</small><br> | <br><small>Cover.</small><br> | ||

[[image:1989-02-23 contents page blurb.jpg|280px|border]] | |||

<br><small>Contents page blurb.</small><br> | |||

{{Bibliography notes footer}} | {{Bibliography notes footer}} | ||

Revision as of 19:46, 14 June 2013

|